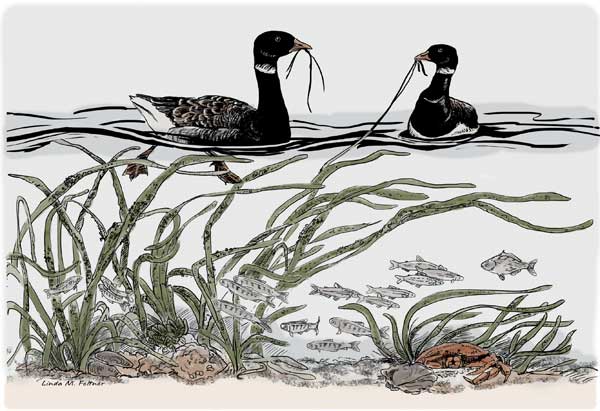

Eelgrass beneath the bay

Eelgrass nurtures and nourishes the nearshore food web

U.S. Geological Survey photo

With little fanfare, ribbon-like eelgrass creates some of the most productive coastal habitats in the world. Nutrient-rich local mudflats in Fidalgo Bay, Samish Bay, and Padilla Bay offer ideal eelgrass environments.

A member of the seagrass family, long-leaved eelgrass is not really a “grass,” but a marine flowering plant that forms expansive green meadows in our shallow, sun-lit coastal waters.

Beneath the surface, eelgrass buffers wave action, stabilizes sediments, and offers food, shelter, and shade for a complex community of important marine species. Washington’s multi-million-dollar fish and shellfish industries depend on our valuable eelgrass meadows.

Notice the eelgrass beds in the shallow water below you. After a storm, you’ll see eelgrass floating on the water and washed up on shore.

Illustration: Linda M. Feltner

Eelgrass provides a valuable “ecosystem service” by capturing the sun’s energy and passing it up the food chain. For example, it’s an important food source for Brant geese.

A Species of Concern

Eric Hoeupel photo

Is our eelgrass declining?

Eelgrass is recognized as a key indicator of regional ecosystem health. Studies suggest an overall decline in eelgrass sites throughout Puget Sound. Padilla and Samish bays, however, are among a handful of large, healthy eelgrass beds that, together, make up some 30% of the Sound’s total eelgrass.

How do we bring it back?

We can’t stop natural eelgrass losses from storm damage and disease. However, we can tackle the harmful effects of shoreline development, runoff, shading, dredging, and boat traffic. Pollution and excess nutrients from runoff reduce oxygen, promote harmful algae blooms, and block sunlight needed by eelgrass habitats.

Let’s preserve what we have now!

Eelgrass grows in the vulnerable coastal zone. When disturbed, it dies rapidly, along with the species that live under its protective canopy. Today, state and federal laws protect eelgrass habitats. Though their survival is not guaranteed, new beds must be planted to replace eelgrass damaged by shoreline activity.

M.J. Adams photo

Zostera marina (large blade, right) is a native seagrass that grows in the subtidal zone of shallow coastal areas. Its smaller, non-native cousin Zostera japonica (left) lives closer to shore in the intertidal zone.

Page-top photo: National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration